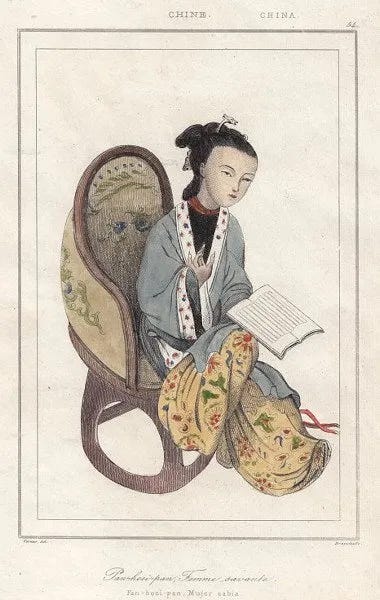

Ban Zhao

The Female Scholar Who Structured Confucian Womanhood in the Eastern Han Dynasty/ Powerful women of China Series

Ban Zhao the Female Scholar Who Structured Confucian Womanhood in the Eastern Han Dynasty

The Paradox of Ban Zhao

Ban Zhao’s life was a paradox in Chinese history. She was first a woman. A phenomenal woman of unparalleled scholarly achievement and political influence. She is credited as the author of the definitive text dictating female submission and domestic confinement. To resolve this paradox, one must move beyond anachronistic judgments and place her work within the specific intellectual and social context of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE).

Eastern Han dynasty was characterized by the consolidation of Confucian state orthodoxy, the increasing importance of the literati class, and corresponding anxieties about social order and familial harmony.[1] Ban Zhao, born into the famous Ban family of scholars and officials. She was uniquely qualified to address these social anxieties.[2] Her life’s work included completing the Han Shu History of the Former Han after her brother’s death, serving as tutor and advisor to Empress Deng, and engaging in scholarly debates at court. She demonstrated an exceptional mastery of the Confucian tradition.[3] This essay will analyze how Ban Zhao channeled this mastery into Lessons for Women, transforming diffuse social expectations into a formalized Confucian curriculum for women.

Through a close examination of her synthesis of classical ideals, her pragmatic adaptation of li, and her own embodiment of “cultivated rationality,” we can understand her not as a patriarchal collaborator but as a conservative reformer working from within the system to articulate a dignified, ethical path for women in a Confucian world.[4]

Literature Review: Scholarly Perspectives

Academic scholarship on Ban Zhao has evolved from foundational biography to nuanced philosophical and historical critique. Early works in English, such as those by Dorothy Perkins and Barbara Bennet Peterson, established the basic facts of her life and her significance as a historian and author.[5] Bret Hinsch’s biographical work provides a more recent, concise summary, solidifying the standard narrative.[6]

Modern scholarship focuses mainly on her writings, not her gender. Jane Donawerth discusses Ban Zhao within a global history of women’s rhetorical theory, treating her as a conscious author constructing ethical arguments.[7] The most fundamental textual analysis comes from Yu-shih Chen, who recontextualizes the Nüjie as a “historical template” rather than an innovation, arguing it formalized existing elite practices of li.[8] This description is supported thematically by Lisa Raphals’s work on virtue, which provides the broader philosophical discourse on exemplarity that Ban Zhao entered.[9] Jack L. Dull’s study of Han marriage law offers the crucial social and legal backdrop, revealing the pragmatic concerns about inheritance and family stability that reinforced her recommendations.[10]

Modern academic sources address her paradoxical legacy. Lily Xiao Hong Lee analyzes her role in formulating long-lasting controls, while Tienchi Martin-Liao surveys the genre of women’s education handbooks she initiated.[11] Bret Hinsch explicitly traces her “lasting influence” on social practice.[12] Bettina L. Knapp and others highlight her literary persona and agency, using her poetry and memorials to present a fuller picture of her life and accomplishments.[13] Together this literature shows a trajectory from seeing Ban Zhao as a biographical subject to understanding her as a collaborator whose work must be read within specific historical, legal, and philosophical frameworks.

Historical and Intellectual Context: The Ban Family and Han Orthodoxy

Ban Zhao’s philosophies cannot be separated from her familial context. The Ban family were custodians of Confucian orthodoxy. Her father, Ban Biao, began the monumental Han Shu, a project continued by her brother, Ban Gu, and finally completed by Ban Zhao herself. This deep immersion in historiography was the Confucian discipline par excellence for deriving moral and political lessons. This facilitated and shaped her worldview. Even though she was a woman she was educated in orthodox Confucian scholarship. Writing history was an act of Confucian stewardship. It was expected of Confucian scholars to create an of ordered concise past to guide the present.[14]

During the Eastern Han dynasty, Confucianism was firmly embedded as state ideology, with an emphasis on filial piety, social hierarchy, and the alignment of domestic order with political stability. This was a deeply patriarchal society. The Lienü zhuan , Biographies of Exemplary Women, had already established a catalog of female virtue. However, as Robin Wang’s anthology illustrates, discourses on women in pre-Qin and Han thought were diverse, often embedded in broader debates about yin-yang correlations and social roles.[15] Ban Zhao’s task was to concentrate this complex inheritance into a clear, actionable guide for women. Her unique position allowed her to do so not as an abstract philosopher, but as a knowledgeable insider addressing the practical challenges of maintaining an elite household. The elite household was the fundamental unit of the Confucian social order. A man who did not have an orderly home and family life was not respected in any form.

Lessons for Women: A Confucian Synthesis for the Female Sphere

In Lessons for Women, Ban Zhao performs a concise creation of Confucian principles, translating them into a specifically female domain. The text is structured around core virtues: humility, resignation, subservience, and industriousness. However, these are not presented as inherent inferiority but as active and learned disciplines essential for familial harmony, which is the ultimate Confucian good.

Ritual (Li) as the Foundation of Female Conduct

Chen’s argument that the Nüjie is a “historical template” of li is a vital argument.[16] Ban Zhao takes the abstract concept of ritual propriety and applies it to the workings of female life. She addressed speech, demeanor, clothing, and household service. For example, her instructions for a wife’s behavior toward her husband and in-laws are precise enactments of the Confucian emphasis on differentiated roles and respect. This codification served a dual purpose: it provided women with a clear, virtuous roadmap, and it standardized expectations, potentially protecting women from arbitrary criticism by anchoring their conduct in classical precedent.[17] This is important to note, because during Ban Zhao’s time the society was patriarchal and women were considered property. Having this guide was a way to protect women from arbitrary abuses and neglects. In so much as the text explains female behavior standards, it also outlines the requirements of the husband. He was just as much held accountable as his wife or wives.

Reinterpreting the Yin-Yang Correlation

Ban Zhao emphasizes the ubiquitous yin-yang paradigm but subtly recalibrates it. While accepting the association of male with yang (dominant, firm) and female with yin (yielding, receptive), she emphasizes their interdependence and mutual necessity for cosmic and social harmony. She writes, “Yet only by the conjunction of husband and wife can the relations of mankind be preserved.”[18] This framing elevates the wife’s role from mere servitude to a partnership with distinct, complementary responsibilities. Her virtue ensures the prosperity of the lineage, a matter of supreme importance in Confucian thought. Raphals notes, this connects female virtue directly to the foundational value of familial continuity.[19]

Education and Rational Moral Agency

Perhaps the most Confucian and progressive aspect of Ban Zhao’s work is her insistence on female education. She laments that girls are not taught the classics and argues for their education from age eight, focusing on ritual propriety and classical models.[20] This is not a call for literary self-expression but for moral cultivation. A woman who understands the reasons behind ritual can internalize and perform it sincerely, thereby becoming a true moral agent within her sphere. This aligns with the core Confucian belief in educability and self-cultivation as the path to virtue. Donawerth correctly identifies this as a rhetorical theory for women, teaching them to “cultivate themselves” to persuade through virtue and maintain harmony.[21] Ban Zhao’s own life was the ultimate testament to this principle. She had privilege and her formidable education was the source of her authority.

The Legacy and Paradox Revisited

Ban Zhao’s legacy is monumental and limited. She was limited by the social constructs of her time. However, she was a brilliant scholar and paved the way for female scholars in later dynasties. Hinsch and Lee discuss, Lessons for Women became the foundational text for female education for centuries, its precepts reinforced by later dynasties.[22] It provided a Confucian sanctioned ideology that limited women’s autonomy and legally enforced their subordination. Yet this outcome must be separated from Ban Zhao’s immediate intent. Writing in a time of political and social consolidation, she sought to dignify and stabilize the female role within the only ethical framework available to her: a flourishing Confucianism.

Her own biography, as analyzed by Knapp and evident in her court service, resolves the paradox by demonstrating the power available to a woman who perfectly embodied cultivated virtue and intellectual prowess.[23]She did not argue for women’s entry into the male public sphere of administration. She knew for her time and society it would not be accepted. She instead argued that the private sphere of the family was a realm of grave ethical importance, requiring disciplined, educated, and virtuous stewardship. In systematizing the Confucian path for women, she made it coherent, teachable, and, in her own person, profoundly respectable. She also paved the ay for female education and literacy.

Conclusion

Ban Zhao’s contribution to Confucianism was her successful systematization of female ethics. She was not a radical but a consummate insider who, drawing upon her deep knowledge of history, classics, and ritual, organized prevailing norms into a clear, authoritative handbook. Her work anchored female identity firmly within the Confucian universe of li, virtue, and familial duty. While many think she did not do enough for women she did what she could to preserve their respect and elevate their status in a way that would be accepted in a patriarchal society.

Lessons for Women undoubtedly served to restrict women’s lives for generations, its genesis was more complex than mere imposition. It represented an attempt to provide women with a dignified, morally fundamental role and a path to ethical perfection within the constraints of Han society. Ban Zhao herself remains the ultimate example of the system she outlined. She was a woman whose mastery of tradition granted her a voice that has echoed for two millennia. Future research could further explore the tensions between her historical writings and her moral instructions, probing how her methodology as a historian influenced her construction of an ideal female social order. To study Ban Zhao is to grasp the intricate ways in which authority, tradition, and gender were negotiated at the very heart of the Confucian tradition.

Bibliography

Chen, Yu-shih. “The Historical Template of Pan Chao’s Nü chieh.” T’oung Pao 82, no. 1/3 1996. 229–257.

Donawerth, Jane. Rhetorical Theory by Women Before 1900. Lanham, Maryland. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

Dull, Jack L. “Marriage and Divorce in Han China: A Glimpse at ‘Pre-Confucian’ Society.” Chinese Family Law and Social Change in Historical and Comparative Perspective, edited by David C. Buxbaum, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978. 23–74.

Hinsch, Bret. “Ban Zhao.” In Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography, edited by Kerry Brown, Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire, 2014. 1:222–235.

Women in Early Imperial China. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Knapp, Bettina L. “Pan Chao: Poet, Historian, and Moralist.” Images of Chinese Women: A Westerner’s View, Troy, N.Y.: Whitston Publishing Company, 1992. 79–97.

Lee, Lily Xiao Hong. “Ban Zhao (48-c. 120): Her Role in the Formulation of Controls Imposed Upon Women in Traditional China.” The Virtue of Yin: Studies on Chinese Women, Broadway, NSW, Australia: Wild Peony, 1994. 11–24.

Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. New York, N.Y.: Roundtable Press, 2000.

Peterson, Barbara Bennet. Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2000.

Raphals, Lisa. Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998.

Wang, Robin, editor. Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period through the Song Dynasty. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2003.

[1] Bret Hinsch, Women in Early Imperial China Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002). 3-15.

[2] Barbara Bennet Peterson, Notable Women of China: Shang Dynasty to the Early Twentieth Century Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2000. 98-102.

[3] Bret Hinsch, “Ban Zhao,” Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography, ed. Kerry Brown Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire, 2014. 1:225-228.

[4] Jane Donawerth, Rhetorical Theory by Women Before 1900 Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002. 17-19.

[5]Dorothy Perkins, Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture New York, N.Y.: Roundtable Press, 2000, 28; Peterson, Notable Women of China, 98-105.

[6] Hinsch, “Ban Zhao,” 222-235.

[7] Donawerth, Rhetorical Theory by Women Before 1900, 337.

[8] Yu-shih Chen, “The Historical Template of Pan Chao’s Nü chieh,” T’oung Pao 82, no. 1/3 1996. 229-230.

[9] Lisa Raphals, Sharing the Light: Representations of Women and Virtue in Early China Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998, 1-30.

[10]Jack L. Dull, “Marriage and Divorce in Han China: A Glimpse at ‘Pre-Confucian’ Society, Chinese Family Law and Social Change in Historical and Comparative Perspective, ed. David C. Buxbaum Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978. 23-74.

[11]Lily Xiao Hong Lee, “Ban Zhao (48-c. 120): Her Role in the Formulation of Controls Imposed Upon Women in Traditional China,” The Virtue of Yin: Studies on Chinese Women Broadway, NSW, Australia: Wild Peony, 1994, 11-24; Tienchi Martin-Liao, “Traditional Handbooks of Women’s Education,” Woman and Literature in China, ed. Anna Gerstlacher et al. (Bochum: Brockmeyer, 1985), 165-189.

[12] Hinsch, Women in Early Imperial China, 117-135.

[13] Bettina L. Knapp, “Pan Chao: Poet, Historian, and Moralist,” Images of Chinese Women: A Westerner’s View Troy, N.Y.: Whitston Publishing Company, 1992, 79-97.

[14]Hinsch, “Ban Zhao,” 224.

[15]Robin Wang, ed., Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre-Qin Period through the Song Dynasty (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2003), ix-xviii.

[16] Chen, “The Historical Template of Pan Chao’s Nü chieh,” 229-257.

[17] Raphals, Sharing the Light, 155-180.

[18] Translated by Nancy Lee Swann, Pan Chao: Foremost Woman Scholar of China New York: Century Co., 1932, 84.

[19] Raphals, Sharing the Light, 165.

[20] Donawerth, Rhetorical Theory by Women Before 1900, 337.

[21]Donawerth, 18.

[22] Hinsch, Women in Early Imperial China, 130; Lee, “Ban Zhao,” 11.

[23] Knapp, “Pan Chao: Poet, Historian, and Moralist,” 79-80.

Bao Zhao is the second instalment in the Prominent Women of Ancient China. Please visit Empress Wu in the first essay.

White Rabbit Musings is my labor of love. This publication is reader supported. All articles will remain free domain, however if you would like to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or buying me a book. Thank you so very much for reading. I appreciate your time.

This is fascinating. You did a lot of hard work here!!