Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Emperor Xuanzong’s Cypress Tree

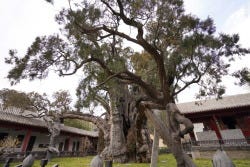

The cypress tree at the Xuanyuan Temple, also known as the Yellow Emperor’s tomb, is a significant historical and cultural landmark. It is believed to be the oldest surviving cypress tree in China and, as confirmed by British forestry expert Roper in 1982, it is the largest and oldest cypress tree in the world. The tree is approximately nineteen meters tall with a thickest part measuring 11.6 meters in perimeter. It has been put under protection and is under radar tests to ensure its extensive root and branch systems. The tree was artificially planted, like other ancient arborvitaes in the temple, and its root and branches were found to be more extensive in radar tests conducted in 2017 and 2023. Trees with identical genes to the ancient tree have been developed with the cloning technology applied.[1]

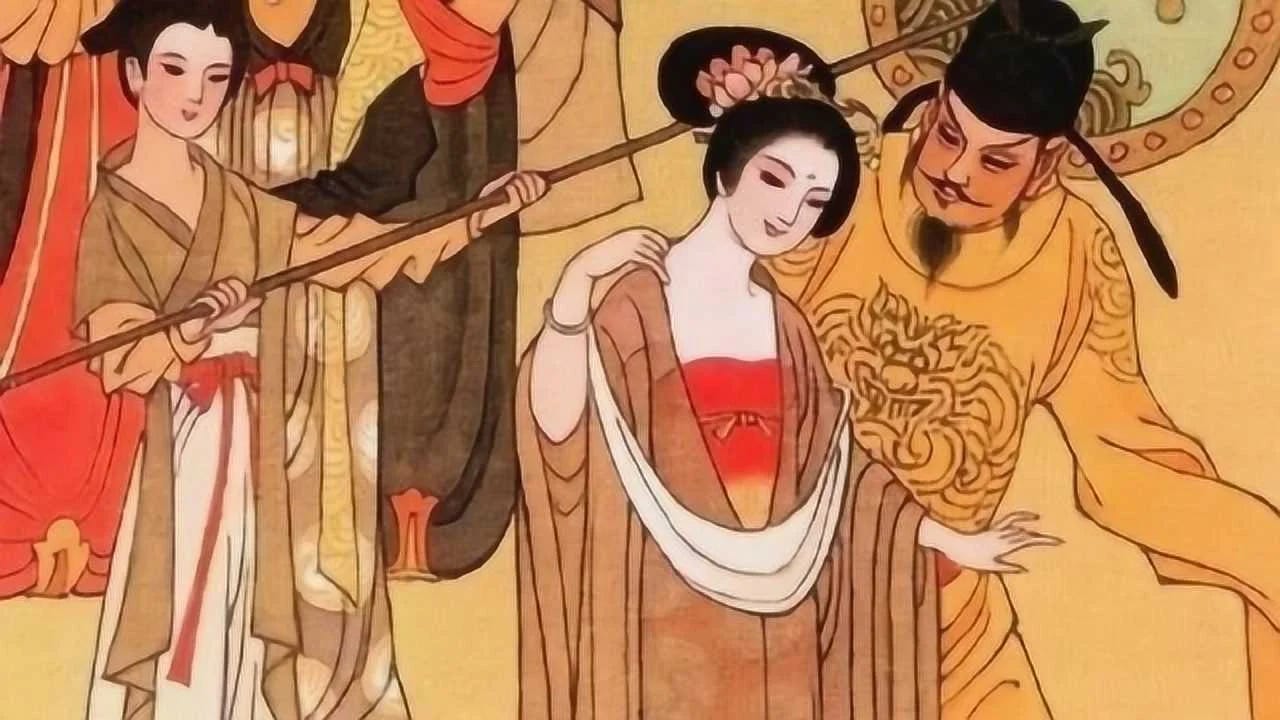

The story of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty and his beloved consort Yang Guifei is one of the most enduring and tragic love tales in Chinese history; a romance that has captivated poets, playwrights, and artists for centuries. Their love saga is often remembered for its tragic end, and the ruin of an empire. Yang Guifei’s death, a forced execution during a military revolt, ended their romance. However, a quieter, more poignant symbol of their bond exists in the imperial gardens of the old capital, Chang’an. There, according to historians, Xuanzong planted a cypress tree in memory of his lost love. This single, living monument encapsulates the profound personal grief of an emperor and the larger political and cultural currents of his reign, a period marked both the dazzling zenith and the devastating decline of the Tang Dynasty.

Emperor Xuanzong’s long reign, 712-756, began as a golden age. His younger years are remembered for its administrative competence and flourishing arts. His later years were characterized by an intense devotion to Yang Guifei that, in the eyes of many court officials and historians, led him to neglect his imperial duties.[2] The An Lushan Rebellion forced the court to flee, war and violence broke out, the people suffered loss of homes, lives, and stability. To secure support to retake his country, Xuanzong was forced to have his beloved executed. The soldiers and courtiers would not agree to suppressing the rebellion unless Yang Guifei was executed. They hoped it would bring stability back to the court.

However, this was not the case, Emperor Xuanzong never recovered from the loss of his beloved consort. He did not govern long after the rebellion, his son instead ascended to the throne. His grief was his final undoing, after fleeing to Sichan during the An Lushan rebellion, he relinquished the throne to his son Li Heng in 756. The army declared Li Heng Emperor Suzong in Lingwu. He spent his entire reign trying to quell the rebellion. In 763, his son Emperor Daizong finally ended the rebellion, but the Tang dynasty never recovered. Xuanzong died in 763, thirteen days before his song Li Heng.

The cypress tree, planted after Yang Guifei’s death, stands as a testament to Emperor Xuanzong’s personal obsession.

In classical Chinese tradition, the cypress is an evergreen, symbolizing longevity, fidelity, and endurance. By planting it, Xuanzong was creating a living, enduring monument to his love, a permanent fixture in the landscape that defied the finality of her death. This tree-planting act symbolized his need to preserve her memory and was also an act of rebellion in his refusal to forget her. This longing and outward show of grief, though criticized by court and military officials, was widely utilized in poetry, theater performance, music, and literature in China. Xuanzong’s love was seen as a shame on the royal family, and the destruction of the Tang Dynasty.

He was especially obsessed with finding her spirit. He summoned Taoist priests to look for her spirit/soul so he could reunite with her, apologize, spend time with her.

Hong Sheng’s The Palace of Eternal Youth, immortalizes this act, portraying Xuanzong’s desperate, otherworldly quest to reunite with Yang Guifei’s spirit, reinforcing the idea of a love that sought to transcend mortality itself.[3]

The cypress tree was more than just a private memorial; it was planted in the politically charged space of the imperial gardens. It was a small act of rebellion. These gardens were not only decorative but also powerful symbols of the emperor’s authority and connection to the cosmic order. Historian D.L. McMullen notes, “the imperial gardens were places where “recollection” of the past was intrinsically linked to the state’s legitimacy.”[4] Xuanzong’s act of planting a tree for his disgraced consort could be seen as a highly personal, and perhaps politically charged, intrusion into a state-sanctioned space. It was a public declaration of a private grief for a woman whom many blamed for the catastrophe that had nearly toppled the dynasty.

Du Fu, one of Tang dynasty’s greatest poets, lived and witnessed these events. He authored many poems with a sense of melancholy about the gardens and the capital, the loss of social decorum, and the need for more humanitarian support of the common people. His verses serve as elegies for a lost golden age, as well as a historical record for future generations.[5]

The cypress, in this context, becomes a silent witness to this fall, a living relic of the “everlasting sorrow” by poet Bai Juyi, Stephen Owen translates and commentary identifies this as the central theme of their story.[6] The everlasting sorrow of lost love and a lost kingdom.

The romance of Xuanzong and Yang Guifei has been carried through time, from high literature to popular art. Their love story spread beyond China, inspiring art, and literature in places like Japan. In 1766, the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Suzuki Harunobu created Parody of the Romance of the Chinese Emperor Xuanzong and the Lady Yang Guifei.[7] This work shows how the tale traveled beyond China’s borders, being adapted and reimagined in diverse cultural contexts. Harunobu’s “parody” reflects a fascination with the exotic and tragic dimensions of the story. Though the cypress tree may not appear, the lovers’ story endures through repeated artistic reinterpretation.

The cypress tree planted by Emperor Xuanzong is a historical footnote that speaks of a love through the centuries. It connects the intimate, human emotion of grief with the grand sweep of history. It represents an emperor’s attempt to immortalize a love that defined his reign and, in the eyes of history, ultimately compromised it. From the state gardens of Tang China to the pages of poets and the woodblocks of Edo Japan, the story of Xuanzong and Yang Guifei, and the symbolic tree that memorialized it; remains a timeless narrative of how personal passion can become irrevocably entangled with the fate of an empire.

Bibliography

李虹睿. “Gone, but Far From Forgotten.” https://en.chinaculture.org/2017-04/03/content_981150.htm.

Hong, Sheng. The Palace of Eternal Youth. Translated by Xianyi Yang and Gladys Yang. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1955.

McMullen, D. L. “Recollection without Tranquility: Du Fu, the Imperial Gardens and the State.” Asia Major 14, no. 2 2001. Pp. 189–252.

Owen, Stephen. “The Everlasting Sorrow.” Calliope. Peterborough: Cricket Media, 2003.

Suzuki Harunobu. Parody of the Romance of the Chinese Emperor Xuanzong and the Lady Yang Guifei. 1766.

Wright, Edmund. “Xuanzong.” A Dictionary of World History. Oxford University Press, 2006.

[1] 李虹睿, “Gone, but Far From Forgotten,” https://en.chinaculture.org/2017-04/03/content_981150.htm.

[2]Edmund Wright, Xuanzong, A Dictionary of World History ,Oxford University Press, 2006.

[3] Sheng Hong, The Palace of Eternal Youth, trans. Xianyi Yang and Gladys Yang Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1955.

[4] D. L. McMullen, Recollection without Tranquility: Du Fu, the Imperial Gardens and the State, Asia Major 14, no. 2 2001. 191

[5] McMullen, Recollection without Tranquility, 205-208.

[6] Stephen Owen, The Everlasting Sorrow, Calliope Peterborough: Cricket Media, 2003.

[7] Suzuki Harunobu, Parody of the Romance of the Chinese Emperor Xuanzong and the Lady Yang Guifei, 1766.

Thank you for reading, I appreciate your time. Many blessings.

This piece is powerful because it shows that this is not simply a story of love, but a story of those who became enemies of love. You have beautifully connected personal grief with political fear and power, showing how love was treated as a weakness and silenced in the name of stability. The cypress tree stands out as a quiet but lasting act of resistance, proving that love can be suppressed, but never erased. What makes this work especially compelling is how it reminds us that when systems and people destroy love, they often destroy themselves as well. This is thoughtful, well-researched, and deeply moving. Thank you for telling this story with such clarity and depth.

I’ve never known much of China’s history, though I’ve always been aware of how rich and layered it is. I love reading your posts because you make that history feel alive. The way you wove grief, memory, and the cypress tree into both personal devotion and the fate of an empire was quietly powerful. You have a gift for turning history into something felt, not just learned. Thank you for sharing this.